1571: The Spanish Conquest and Founding

On June 3, 1571, Miguel López de Legazpi, the first Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines, established Intramuros as the capital of Spanish colonial rule in Asia. The choice of location was strategic: Manila already served as an important port and trading hub under pre-colonial chieftains, but the Spanish recognized it as the ideal base for controlling the archipelago and projecting Spanish power across the Pacific.

The Spanish immediately began constructing fortifications--massive stone walls designed to withstand both external invasion and internal resistance. Construction took decades, ultimately completed in 1606. The walls stretched 2.5 miles around the perimeter, reaching up to six meters (nearly 20 feet) thick. These were not merely defensive structures; they were statements of permanence, declarations that the Spanish intended to stay forever. Every stone represented centuries of Spanish masonry tradition, every fortification echoed European military architecture perfected through centuries of conquest and defense.

The Spanish laid out Intramuros using the gridiron plan--the same rational, geometric urban design that Spanish conquistadors had used throughout their American colonies. Straight streets intersected at right angles, creating a grid that imposed order and control. The plan was so effective that it became the template for all subsequently established towns in the Spanish Far East. Intramuros was not merely a city; it was a blueprint for Spanish colonial urbanism exported across Asia.

The Colonial City: 1571-1898

For over three centuries, Intramuros functioned as the complete Manila--the entire city meant to matter. Within the walls, the Governor-General exercised supreme authority over the Philippines and, at times, over Spanish territories as far as Guam and the Mariana Islands. The city housed the palace of the Governor-General, the seat of the ecclesiastical hierarchy (the Archbishop's residence), government offices, military barracks, and the homes of Spanish elites. Outside the walls, in areas like Binondo and other districts, common Filipinos and Chinese merchants lived in segregated communities under Spanish supervision.

Intramuros was a city explicitly designed to reinforce hierarchy. Spanish colonizers lived in elegant Bahay na Bato (stone houses) within the walls, while the colonized population lived in wooden structures outside. The architectural distinction was visual testimony to colonial power--stone for conquerors, wood for the conquered. This spatial segregation made the inequality of colonization literally visible, embedded in urban form.

Yet despite its rigid hierarchies, Intramuros was also cosmopolitan. The Manila Galleons brought traders from China, merchants from Mexico, sailors from Spain and Portugal. Intramuros became a multilingual, multi-ethnic hub where Spanish colonial power intersected with global trade. The Parian (a Chinese merchant quarter) developed outside the walls, transforming Manila into a truly international city. This cosmopolitanism paradoxically coexisted with brutal colonial control--Manila was simultaneously cosmopolitan and oppressive, wealthy and exploitative.

Religious Architecture: The Churches of Intramuros

Within Intramuros' walls, the Spanish built eight magnificent churches representing different religious orders. These structures were not mere places of worship; they were statements of Spanish religious authority and the fusion of faith with political control. The churches embodied European architectural traditions adapted to tropical climates and local materials, creating a distinctive Philippine-Spanish baroque style.

San Agustín Church, completed in 1607 after 44 years of construction, stands as the crown jewel. Its walls of volcanic stone (called molajon) have survived earthquakes, fires, and wars. The church is the oldest stone church in the Philippines and remains one of only four Baroque Churches of the Philippines inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Walking into San Agustín is to step into a preserved moment of Spanish colonialism--the ornate altar, the baroque ornamentation, the soaring ceilings all speak to the immense resources Spain devoted to religious authority.

The other seven churches--built by the Dominicans, Franciscans, Jesuits, and other religious orders--have not survived intact. Their destruction in 1945 represents not merely loss of buildings but erasure of centuries of spiritual and artistic tradition. Only the physical resilience of San Agustín's volcanic stone allowed it to survive where other churches perished.

Fort Santiago: The Heart of Power

At the northern edge of Intramuros stands Fort Santiago, perhaps the most historically charged location in the walled city. Built in 1571 simultaneously with Intramuros' founding, Fort Santiago was the residence of the Governor-General and the seat of Spanish military and administrative power. Its angular bastions, designed according to European military science, projected Spanish technological superiority. The fort's cannons commanded the Pasig River, ensuring Spanish control over waterborne commerce and potential invasion.

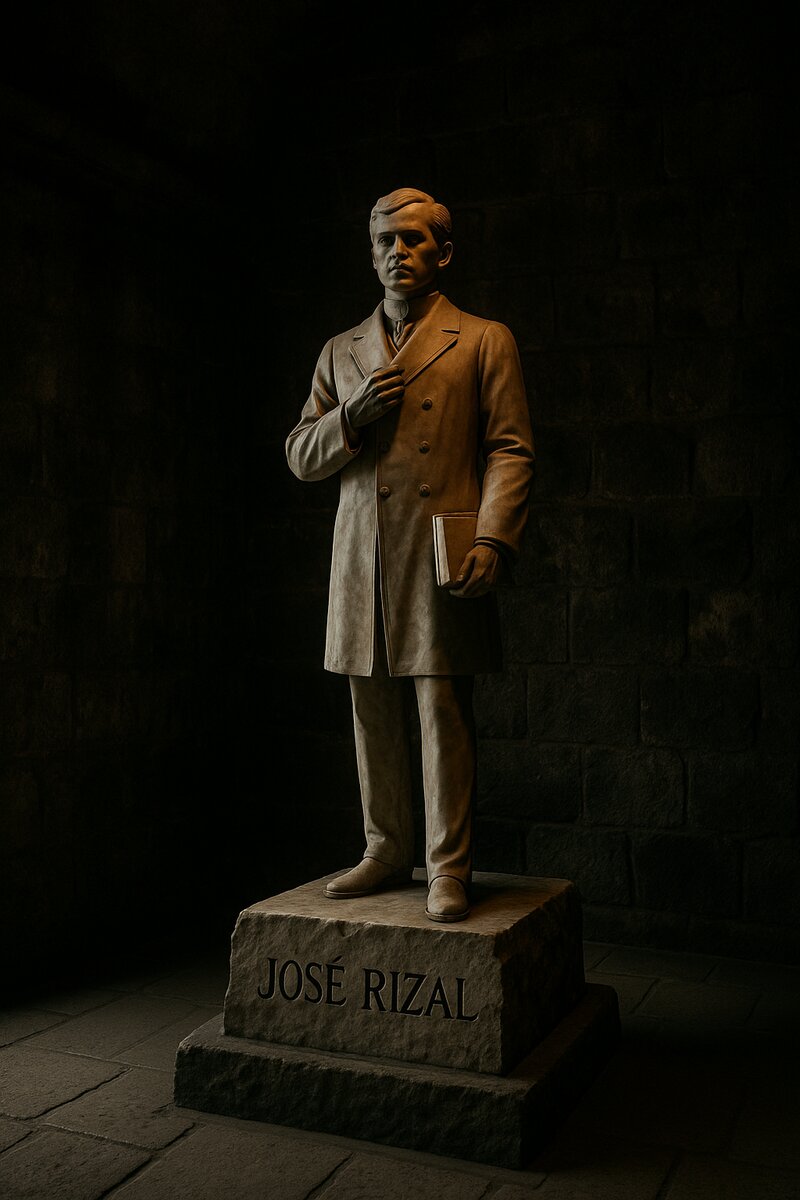

Fort Santiago carries profound significance in Filipino national consciousness because of one man: Dr. José Rizal, the Philippines' national hero. Rizal, a writer and intellectual who advocated peaceful reform of colonial rule, was imprisoned in Fort Santiago's dungeons and executed there on December 30, 1896. His execution transformed Fort Santiago from a symbol of Spanish military power into a symbol of Filipino resistance and martyrdom. The spot where Rizal stood before his execution, the view he had of the Pasig River on what would be his last day--these details are venerated in Filipino collective memory.

During the American occupation (1898-1946), Fort Santiago became a garrison and military headquarters. The American military, like the Spanish before them, recognized its strategic and symbolic importance. The fort survived the Battle of Manila relatively intact, unlike much of the rest of Intramuros, and thus bears witness to its own history--both as a monument to Rizal and as a physical reminder of military occupation across centuries.

March 1945: The Battle of Manila and Total Destruction

On March 3, 1945, American and Japanese forces collided in Manila during the Pacific War. The battle for Intramuros was apocalyptic. For three weeks, artillery fire, aerial bombardment, and close-quarters urban combat raged within the walled city. The Japanese military used Intramuros' fortifications to mount a desperate, final defense. American forces, determined to liberate Manila and push toward Japan, responded with overwhelming firepower.

The result was nearly complete devastation. Over 95% of Intramuros' structures were destroyed. The medieval walls--those 2.5-mile stone fortifications that had stood for over three centuries--were 40% demolished. The eight grand churches built by religious orders over centuries were obliterated, leaving only rubble. Thousands of civilians died, trapped or caught in the crossfire. The battle killed more people than the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would a few months later, yet remains less known globally.

Walking through photographs of Intramuros in March 1945 is to witness the complete erasure of an urban landscape. Street after street shows nothing but rubble--the baroque churches, the stone houses, the government buildings, the Governor's Palace all reduced to debris. It's a landscape that looks more like Pompeii after Vesuvius than a modern city. History didn't end politely; it was bombed into fragments.

Yet San Agustín Church stood. Its volcanic stone walls, built to withstand earthquakes, somehow survived the battle's fury. This single church survived becomes a powerful symbol--of resilience, of the endurance of faith, of how sometimes even in total destruction, something sacred remains.

Rebuilding Ruins: 1946-Present

After the war, the Philippines faced a choice about Intramuros: rebuild it, or leave it as ruins? The decision was to preserve and gradually restore. In 1951, Intramuros was declared a historical monument and Fort Santiago was established as a national shrine through Republic Act 597. President Ferdinand Marcos created the Intramuros Administration (IA) in 1979, officially tasking it with the restoration, administration, and preservation of the walled city.

Reconstruction has been methodical and painstaking. Starting in the 1960s-1980s, the government systematically restored buildings using original materials where possible. New structures have been designed to echo the original architectural vocabulary--maintaining the gridiron plan, the baroque aesthetic, the Spanish colonial feel. The walls themselves have been gradually reconstructed, with original stones reused and supplemented where necessary. Modern restorations sometimes use reinforced cement concrete, but even these maintain the original aesthetic and proportions.

The work continues today, over 75 years after the battle's conclusion. Visitors walking through Intramuros encounter a landscape of ongoing restoration--some buildings fully preserved, others partially restored, a few still showing their war scars as reminders. The IA must balance multiple competing demands: preserving the architectural heritage, maintaining the area as a living, functioning district rather than a museum, and doing so with limited funding.

Living History: Intramuros Today

Modern Intramuros functions as a living heritage district rather than a static museum. Within the walls, residents live in restored colonial homes. Restaurants, shops, and small businesses operate in street-level storefronts. Tour companies guide visitors through the streets. Art galleries and cultural centers occupy restored buildings. The tension between preservation and contemporary use creates dynamic spaces--a baroque church hosting modern art exhibitions, a colonial building housing a contemporary restaurant, ancient walls framing contemporary Manila beyond.

Walking Intramuros today, you encounter layers of time simultaneously. Seventeenth-century stone walls frame twentieth-century scars. Spanish colonial architecture stands within modern Manila's skyline. Japanese artillery damage remains visible on some walls, refusing to be completely erased. The restored churches glow with careful preservation while empty lots mark where other buildings have not yet been rebuilt. It's not a perfectly preserved colonial theme park; it's a real place struggling with its history.

What Intramuros Means Now

Intramuros today represents something more complex than nostalgia for Spain or appreciation of colonial architecture. It is a record of conquest, a monument to those who resisted, a testament to resilience, and an ongoing project of preservation and remembrance. The walls that once confined the colonized now preserve the colonized nation's heritage. Fort Santiago transformed from a symbol of Spanish military authority into a shrine to Filipino martyrdom.

For Manila residents and visitors, Intramuros asks difficult questions: How do we honor historical preservation while acknowledging the violence of colonization? How do we live alongside our history rather than simply consuming it as tourism? How do we remember those who died in 1945 without treating their deaths as mere historical details? These questions remain unanswered, suspended within the stones of Intramuros, waiting for each generation to grapple with them anew.