Origins: From Pre-Colonial Times to Spanish Influence

Before the Spanish arrived, indigenous Filipino communities were already making sinigang. The technique is simple and ancient: stew meat or seafood with acidic fruits and vegetables until flavors meld and the broth becomes rich. The Filipino islands have always had access to souring agents--tamarind (sampalok), unripe mangoes, calamansi, and guava grow prolifically. Filipinos learned to harness these natural acids not just for flavor, but as a preservation method in a tropical climate without refrigeration.

What changed during the Spanish colonial period (1565-1898) was the ingredient profile, not the technique. The Spanish introduced new crops and ingredients, including tamarind pods, which became the dominant souring agent for sinigang. While indigenous Filipinos used whatever souring fruits were at hand, the Spanish integration of tamarind created a more standardized version of the dish. The word sinigang itself predates Spanish arrival, suggesting that the cooking method existed before the ingredient standardization.

The dish that emerged from this period--pork sinigang with tamarind--became the template for what we recognize today. But sinigang was never meant to be rigid. It's fundamentally a technique, not a recipe.

The Foundation: How Sinigang is Made

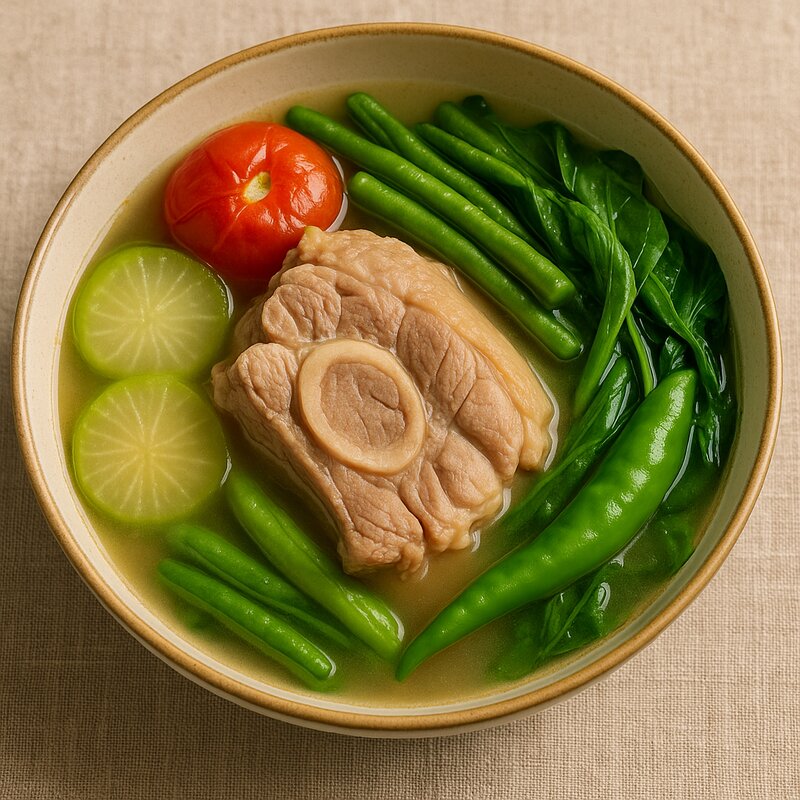

All sinigáng starts with the same principle: acidic broth + protein + vegetables = complete meal. The proportions and ingredients vary wildly, but the framework is consistent.

The broth begins with a souring agent. Tamarind (sampalok) is the most common, but the essence of sinigang is flexibility. You can use unripe mangoes (alimango), calamansi, guava (bayabas), or even pineapple for sweetness balanced with sourness. Some home cooks mix multiple souring agents for complexity.

The protein carries the soup's body. Traditionally pork (especially ribs and shoulder), but also beef, chicken, shrimp, fish, or a mix. Some versions are vegetarian, using mushrooms or tofu as the protein element.

The vegetables are where regionality and family tradition shine brightest. Core vegetables that appear across most variations: okra (okra), taro root (gabi) for starch and body, white radish (labanos) for sweetness, and yardlong beans (sitaw). Beyond these, families add what's available: eggplant, bok choy, malunggay (moringa), cabbage, bamboo shoots, even potato.

The seasoning is typically minimal: garlic, onion, fish sauce (patis), sometimes bay leaves. The magic comes from layering flavors during the long cooking process, not from complex seasoning additions.

Regional Variations: Sinigang Across the Philippines

Tagalog Sinigang (Central Luzon & Manila)

The 'standard' sinigang most Filipinos recognize. Pork (often ribs and shoulder) stewed with tamarind, gabi, okra, radish, string beans. The broth is deep brown-red, glossy with pork fat, and intensely savory-sour. This is the version that dominates Metro Manila restaurants and the one most exported Filipinos reference when they think sinigang. It's comfort in a bowl for Tagalogs, proof that simple ingredients can create profound flavors. Typically served with white rice and fish sauce on the side.

Bicol Sinigang (Bicolandia)

The Bicol region adds its signature element: labuyo peppers (bird's eye chilis). Bicol sinigang is the same technique as Tagalog sinigang, but with heat. The peppers create a subtle burn that builds on the palate. Some Bicolano home cooks also add coconut milk, creating a richer, more complex broth. This variation appeals to those who want sinigang with more personality and punch.

Seafood Sinigang (Coastal Regions)

In fishing communities from the Visayas to Mindanao, sinigang uses what's abundant: fish, shrimp, crab, or mixed seafood. Seafood sinigang cooks much faster than pork (30-40 minutes versus 1.5-2 hours for pork), and the broth becomes lighter, more delicate. The sourness becomes more prominent because there's less pork fat to balance it. Some fishermen's wives add shrimp paste (bagoong) for umami depth. This version appears in local markets and seaside restaurants, and it tastes distinctly of the ocean.

Sinigang sa Bayabas (Guava Sinigang)

Using guava instead of tamarind creates a brighter, more fruity sourness. Guava sinigang is less common in Manila but popular in rural provinces and among home cooks who have access to abundant guava. The broth is lighter in color, more yellow-brown than red-brown. It has a subtle sweetness that tamarind lacks, making it feel more 'home cooked' and less standardized.

Sinigang sa Mangga (Unripe Mango Sinigang)

Using green (unripe) mango as the souring agent creates a more complex sinigang. The mango's tartness is different from tamarind's--slightly more floral, less aggressive. This variation appears in Iloilo and other Panay province areas. It's considered more elegant, less obvious than tamarind sinigang. Families that make this version often do so by necessity (abundance of green mangoes during off-season) and tradition.

Sinigang sa Misô (Miso Sinigang)

A modern fusion variation that adds miso paste alongside tamarind. The miso contributes umami depth and body that makes the broth feel richer. This version appeals to contemporary Filipino palates and appears more frequently in restaurants than in home cooking. It represents Filipino willingness to adopt and adapt ingredients while maintaining the core sinigang identity.

Sinigang sa Kalamansi (Calamansi Sinigang)

Using Philippine limes (calamansi) creates the brightest, most citrusy sinigang. It's rare as a primary souring agent (you'd need many calamansi) but appears in home cooking when fresh calamansi juice is abundant. The broth is pale, almost clear, and the sourness is sharp and immediate rather than the deep, slow sourness of tamarind.

Sinigang in Filipino Food Culture

Sinigang holds a specific place in Filipino eating: it's rarely fancy, never formal, always honest. You eat sinigang on weekday lunches, at family gatherings, when someone is sick (it's considered restorative), and when you're just hungry and need proper food. There's no sauce to make, no special preparation required. You make it when you have time to let things simmer, which means it's also deeply connected to rhythm and presence.

For Filipinos living abroad, sinigang is homesickness made edible. It's the smell that reminds you of your mother's kitchen, the taste that brings back childhood. Many Filipinos can identify 'good' sinigang by a single spoonful--not because there are strict rules, but because they know what their version tastes like, and family is recognizable in food.

In restaurants, sinigang appears on menus as evidence that a place is 'authentic' Filipino. Street stalls and carinderias serve it as comfort food. Fine dining chefs have attempted to 'elevate' sinigang, usually by clarifying the broth or using premium proteins, but the best sinigang often remains the simplest version, made in home kitchens without fanfare.

The Future of Sinigang

Like all traditional dishes, sinigang evolves. Contemporary versions include vegetable-forward sinigang, mushroom sinigang for vegetarians, and fusion takes using unconventional proteins. Some chefs are experimenting with charred or smoked elements, deconstructed presentations, and modern plating. These experiments don't erase sinigang's core identity--they expand what's possible within the framework.

What matters is that the technique remains accessible. Anyone can make sinigang. The barrier to entry is low: you need a pot, heat, and time. This accessibility is why sinigang has survived centuries of change, why it appears across all social classes, and why it will likely continue evolving as long as Filipinos cook.

Sinigang embodies Filipino comfort food philosophy--simple ingredients combined with technique and love create nourishing, satisfying meals.

Where to Eat the Best Sinigang in Manila

The best sinigang is almost always in home kitchens, but Manila has several places where sinigang is treated with respect:

Carinderias in Quiapo and Divisoria markets -- Street food stalls serving sinigang as it's meant to be eaten: quickly, generously, for reasonable money.

Tingin.ph and similar 'authentic Filipino' restaurants -- Places that focus on regional Filipino cooking often make excellent sinigang because they're not trying to innovate; they're trying to preserve.

Cooks' homes -- If you're invited to eat sinigang at someone's house, that's the best version you'll find. Accept enthusiastically.

Making Sinigang at Home

If you want to make sinigang outside the Philippines, you can use tamarind paste (available at Asian markets or online). Use about 1 cup of tamarind paste dissolved in water for a pot of sinigang. The technique is straightforward: brown the meat, add aromatics, add the tamarind-water, then vegetables in order of cooking time. Let it simmer 1.5-2 hours for pork. The longer cook makes the broth richer and flavors more integrated. No complex technique, just time and attention.

Sinigang variations across regions show how climate, available ingredients, and family traditions influence this beloved Filipino dish.