Chinese Merchants and the Parian: Before Binondo (Pre-1594)

Long before Binondo existed, Chinese merchants sailed to Manila seeking profit and opportunity. When Spanish colonizers arrived in 1565, they found Chinese merchants already established in the archipelago's trading networks. The Spanish, understanding the value of trade, permitted Chinese merchants to remain and operate in Manila--but strictly controlled and segregated. These merchants were called sangley (a term derived from Chinese).

The Spanish established the Parian--a merchants' quarter--where Chinese traders lived and operated their businesses outside the Spanish-controlled Intramuros. The Parian was both a commercial center and a segregated ghetto. Chinese merchants sold silks, spices, porcelain, and other goods from Asia to Spanish colonizers and the Spanish colonial elite. They became essential to Manila's economy, yet remained legally restricted, culturally segregated, and viewed with suspicion by Spanish authorities who feared Chinese power and resented their commercial success.

Within the Parian, Chinese merchants lived by their own customs, ate their own food, maintained their own cultural practices. Yet they also encountered Filipino women, began intermarrying, and over generations created a new mixed-race population: the mestizo de sangley (half-Chinese, half-Filipino). These mestizo families, born of both traditions, became mediators between Chinese merchant communities and Filipino populations. Their kitchens would become spaces where two food traditions began merging.

1594: The Birth of Binondo

In 1594, Governor-General Luis Perez Dasmariñas made a strategic decision. The Chinese merchant population in Manila was growing, and Spanish authorities wanted to encourage their integration and Christianization. Dasmariñas relocated sangleys who had converted to Christianity from the crowded Parian to a new area across the Pasig River. This area became Binondo, established officially in 1594 as a settlement for Chinese Christian converts.

The Spanish intended Binondo as a tool of assimilation and control. By moving converted Christians to a new settlement, authorities hoped to gradually integrate them into Spanish colonial society while keeping non-converted Chinese merchants in the Parian. The reality, however, was more complex. Binondo became something the Spanish hadn't fully anticipated: a thriving Chinese-Filipino community where two cultures genuinely merged rather than one dominating the other.

Binondo's population grew steadily. As Chinese merchant families established themselves, as mestizo children were born, as marriages created kinship ties across ethnic lines, Binondo developed its own character. It wasn't Spain imposed on Chinese culture, nor Chinese culture in Spanish territory. It was something new: a Chinese-Filipino synthesis where both traditions influenced everything.

Food in Binondo: Markets, Kitchens, and Fusion

From the beginning, food was central to Binondo's identity. Chinese merchants needed to eat, and they sought the familiar tastes of home. Yet home was thousands of miles away. Chinese cooks in Manila adapted, using available ingredients to approximate home flavors. Filipino women married to Chinese merchants learned to cook Chinese dishes, improvising with what grew locally. Filipino cooks hired by Chinese merchants learned Chinese techniques and tastes. From this constant negotiation emerged fusion dishes--not quite Chinese, not quite Filipino, but genuinely both.

The market that developed in Binondo reflected this fusion. Chinese merchants sold Asian vegetables alongside indigenous Filipino produce. Filipino vendors sold to Chinese cooks. The markets became spaces of exchange where ingredients themselves became cultural mediators. A Chinese merchant shopping in Binondo market encountered pumpkin (native Filipino vegetable) alongside Chinese bitter melon, might purchase both for a single dish, creating something neither purely Chinese nor purely Filipino.

Food merchants and small eateries emerged to serve the diverse Binondo population. Chinese cooks opened stalls selling noodles, rice, and cooked dishes. Over time, these stalls began serving Filipino workers alongside Chinese merchants. The dishes adapted to serve both populations: noodles with soy sauce (Chinese flavor, Filipino adaptation), rice bowls with stir-fried vegetables (Chinese technique, mixed ingredients). Food became the primary language of cultural negotiation in Binondo.

Pancit: The Perfect Chinese-Filipino Fusion

Pancit represents the Chinese-Filipino culinary fusion so completely that many modern Filipinos assume it's indigenous Filipino food. The story of pancit's origins involves China, the Philippines, and the alchemy of cultural merging. Chinese merchants introduced rice noodles to the Philippines as early as the 14th century through trading connections. The Hokkien word for noodles, prepared quickly, was roughly "pian i sit"--quick-fried food, convenient food. This phrase gradually transformed into the Filipino word "pancit."

Pancit is fundamentally a Chinese dish in origin: noodles stir-fried with vegetables and sauce, a technique perfected over centuries in China. Yet Filipino pancit is distinctly different from Chinese stir-fried noodles. Filipino cooks adapted the dish by using soy sauce as the primary seasoning (rather than various Chinese sauces), finishing dishes with calamansi lime juice (a distinctly Filipino acid), and incorporating indigenous vegetables like pechay. Over generations, each region of the Philippines developed its own pancit variation: pancit luglog, pancit bihon, pancit lomi, pancit Iloco. These regional versions represent how Chinese cooking technique was adopted and adapted across the Philippine archipelago.

In Binondo, pancit became the everyday food of working people. Chinese cooks served it to Filipino workers. Filipino women learned to make it. By the time Spanish colonial control ended, pancit had become so integrated into Filipino food culture that it felt entirely Filipino. Today, you can't imagine Filipino celebrations without pancit--served at birthdays with noodles kept long to symbolize long life, at weddings, at fiestas. The dish is simultaneously Chinese in origin, Filipino in execution and meaning, and globally identified as Filipino food. Pancit is the perfect example of cultural fusion--not diminishment of either tradition, but genuine merging where both elements remain visible yet inseparable.

Lumpia and Regional Variations: Adaptation Across Archipelago

If pancit is Chinese noodles adapted to Filipino taste, lumpia represents Chinese pastry reimagined by Filipino cooks. Chinese spring rolls (lūn-piáⁿ in Hokkien) arrived in the Philippines centuries before the modern era, but modern lumpia took distinctive form in Filipino hands. The traditional wrapper--rolled so thinly that you can nearly see through it, made with just flour, water, and salt--became the Philippines' distinctive lumpia wrapper.

Lumpia evolved into countless regional variations. Lumpiang Shanghai (the Manila/Tagalog version) features a thicker wrapper and meat filling, fried until golden. Lumpiang Iloco is paper-thin and served with sauce. Lumpiang gulay (vegetable lumpia) uses vegetable fillings. Lumpiang sariwa (fresh lumpia, not fried) wraps warm ingredients in fresh wrapper. Each regional variation represents how a single Chinese technique (wrapped pastry) was adopted and reinterpreted throughout the Filipino archipelago. The diversity of lumpia shows that cultural fusion wasn't something imposed uniformly; it emerged organically as different regions made dishes their own.

Binondo's Food Culture Today: Where Fusion Became Foundation

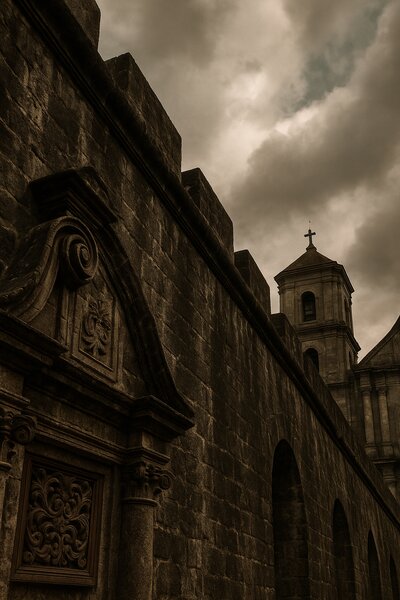

Modern Binondo remains the center of Chinese-Filipino food culture. The neighborhood's narrow streets, historic buildings, and family-run restaurants represent centuries of accumulated culinary tradition. Walk through Binondo's markets and you encounter vendors selling live fish, frozen vegetables, fresh noodles, soy sauce, preserved vegetables--goods serving both the remaining Chinese merchants and Filipino customers who come from throughout Manila to shop.

Binondo's famous restaurants serve two functions: they preserve historical Chinese-Filipino fusion (dishes that have been served for generations, recipes passed down through families), and they innovate, creating new dishes that maintain the fusion spirit while responding to contemporary tastes. In Binondo, you can eat dishes your grandmother's grandmother ate, and you can eat reimagined versions prepared by young chefs returning to neighborhood roots. The neighborhood functions as both archive and laboratory of Chinese-Filipino culinary tradition.

Mestizo de Sangley: The People Behind the Food

The ultimate story of Chinese-Filipino food culture is a story of people. Spanish colonizers created legal categories: sangley (pure-blooded Chinese), mestizo de sangley (mixed Chinese-Filipino), indio (pure-blooded Filipino). These categories were rigid and formal, yet food culture ignored them. In kitchens throughout Manila, in Binondo especially, mestizo de sangley families cooked without thinking much about ethnic categories. A mestizo wife might cook her Chinese father's dishes using her Filipino mother's ingredients, creating something that belonged to both parents.

Over generations, mestizo de sangley became so numerous and so integrated that they eventually became indistinguishable from the larger Filipino population. This process happened through food and family life. Children grew up eating both traditions, neither feeling foreign. Grandchildren forgot which grandparent was Chinese and which Filipino, but continued making the family recipes they'd always known. The fusion became so complete that the very concept of "fusion" became unnecessary--there was just Filipino food, which happened to contain profound Chinese influences.

The Spanish colonizers may have intended segregation and hierarchy, but Binondo became something they didn't anticipate: a space where Chinese and Filipino cultures genuinely merged, where neither dominated, where new cultural forms emerged that belonged fully to both traditions simultaneously.

Siomai, Tikoy, Mami: Other Chinese-Filipino Creations

Beyond pancit and lumpia, countless dishes emerged from the Chinese-Filipino kitchen. Siomai--steamed dumplings with pork filling--are Chinese in origin (from Cantonese tradition) but are served throughout Manila as Filipino food. Tikoy (glutinous rice cake from Chinese tradition) appears at Filipino celebrations. Mami (noodle soup) is Chinese in origin but Filipino in execution. Hopia (pastry with bean filling) is shared between Chinese and Filipino traditions. Each dish carries evidence of cultural exchange, of recipes arriving from China but being adapted to Filipino ingredients, tastes, and culinary contexts.

Contemporary Manila: The Chinese-Filipino Kitchen Lives On

Modern Manila's food scene continues the Chinese-Filipino fusion tradition established over 400 years ago. Young chefs claim Chinese heritage and Filipino citizenship simultaneously, their identities inseparable. Contemporary restaurants in Binondo and throughout Manila serve both traditional Chinese-Filipino dishes and innovative new combinations. These chefs aren't creating fusion cuisine as if doing something new or exotic; they're continuing a tradition that has always been fusion, always been syncretic, always involved merging and adapting across traditions.

Contemporary fusion restaurants throughout Manila--serving dishes that combine Asian techniques with Filipino ingredients, or Filipino traditions with global influences--are working within a framework established centuries ago in Binondo's markets and kitchens. They're continuing a conversation about how to cook when you inherit multiple traditions, how to honor your past while creating something new, how food becomes the vehicle through which genuinely integrated multicultural communities sustain themselves across generations.

The Lesson of the Chinese-Filipino Kitchen

The Chinese-Filipino kitchen teaches something profound about culture: it's not static, not pure, not sealed against outside influence. Culture is what people make when they live together, trade together, marry together, cook together. The Spanish colonizers may have intended segregation and hierarchy, but Binondo became something they didn't anticipate: a space where Chinese and Filipino cultures genuinely merged, where neither dominated, where new cultural forms emerged that belonged fully to both traditions simultaneously.

Pancit contains Chinese history and Filipino innovation, made by families who are simultaneously both Chinese and Filipino. Lumpia wrappers are rolled with techniques brought from China and ingredients available in the Philippines, folded by hands trained in two traditions. These dishes exist at the intersection of cultures, and that intersection is precisely where their authenticity lies. To eat in Binondo is to participate in this history, to taste how cultures merge and become something neither could have been alone.